Adult development: What it is and why it matters today

Think about a time when you went through a significant change or life transition. Maybe you were pulling yourself away from your roots. Maybe you left a prestigious job. Maybe you ended a serious relationship.

What story did you tell yourself about the situation? What meaning did you give it? How did you relate to it then, versus now?

How you answer these questions may shed light on your adult development.

The field of adult developmental psychology captured my attention several years ago - so much so that I decided to pursue it full-time. It’s a complicated, multifaceted field that can be hard to explain, so I wrote this piece to help do just that for those interested in learning about it at a high level.

Adult developmental psychology was born out of the much bigger field of childhood development. This field studies the advancement of the minds of children and adolescents from ages of 0 through roughly 21.

Most fields of science used to believe that after this age, the mind stopped developing - both psychologically and neurologically. But over the last several decades, through the work of developmental psychologists and neurobiologists, we now know that this is not true. Our minds can and do continue to develop into adulthood. The gray matter in our brains is malleable, as is our mindset. With concerted effort, we can change our minds.

The newer field of adult developmental psychology studies the development of the adult mind. It asks questions like:

How do we view our sense of self?

How do we relate to others and the world?

How do we make meaning of the things we experience in life?

How do we respond to our external environment and internal landscape?

What do we believe and where do those beliefs come from?

Several psychologists have paved the way in this field over the last several decades. I’ve found myself most drawn to the work of Robert Kegan and Lisa Lahey, because it’s the easiest to explain and is also backed by research. In this piece, I’ll unpack their work.

A little bit about Robert Kegan and Lisa Lahey

Dr. Robert Kegan is a developmental psychologist and emeritus professor at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Education. His 1982 book, The Evolving Self, laid the foundation of his theory of adult development, which he further refined in his 1994 book In Over Our Heads. Throughout this time period and into the 2000s, Kegan expanded on his theory and with his long-time collaborator, Lisa Lahey, came up with novel ways to both measure and support the advancement of one’s development. Lahey is also a prominent developmental psychologist, author, and faculty member at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. The two co-wrote two books on adult development, most recently Immunity to Change in 2009 (more on that later).

Kegan’s theory of adult development

Kegan’s framework posits that adults can reach three qualitatively different “levels” or plateaus of development. Within each level, our sense of self makes meaning in qualitatively different ways. One consistent through-line across the levels, which can be viewed as a spectrum, is that as our development advances, we become better equipped to see ourselves and the world from increasingly objective perspectives. We become better able to see things with more shades of gray. Our aperture widens and we can hold more, look at more, make sense of more. We become better equipped to look closely at our beliefs, become less attached to them, and form new ones. We become able to see the world more holistically.

The three levels of development in Kegan’s model are the socialized, self-authoring, and transforming mind. For each, I’ll provide a short example using a hypothetical situation of someone who is considering quitting their corporate job.

With the socialized mind, our sense of self is fused with the cultures we live in, particularly those in which we have strong ties to (such as friends, family, and work). The expectations of those around us strongly influence our sense direction and self. We feel a sense of loyalty to the people closest to us. Their values and beliefs are our values and beliefs. When we experience anxiety, it’s often about fear of being abandoned by our tribe.

Job-quitting scenario: You speak with family, friends, and mentors to validate your thinking. If some of them don’t fully support you in your plans, their concerns or anxieties weigh on you.

With the self-authoring mind, we no longer are a fish in water; our sense of self can see the cultures in which we live objectively. We choose to partake in these cultures, or develop our own values and standards by which to live. We’re more independent and self-directed, and hold ourselves to our own expectations. We’re able to recognize the differing perspectives, beliefs, and feelings of others without taking them on as our own. When we experience anxiety from this level, it’s usually about a fear of losing our voice or letting ourselves down.

Job-quitting scenario: You speak with family, friends, and mentors but only to inform them of your plans. If some of them don’t fully support you, you hold compassion for them, recognizing their concerns or anxieties are their experience and not yours.

With the self-transforming mind, our sense of self expands once more and we begin to see the complexities and nuances of the world. We no longer hold our perspectives, beliefs, and values as the ultimate truth. We embrace paradox and hold contradictions. We integrate different belief systems and ideas, recognizing that each individual perspective has drawbacks and blindspots. We are interdependent problem solvers.

Job-quitting scenario: You speak with family, friends, and mentors to solicit their advice and even conflicting viewpoints, recognizing that no one person, including you, has the “right” perspective on such a big decision. However, you ultimately make the final call, understanding that while others may not agree with it, that’s their experience and not yours.

Each of these levels are not like steps on a ladder; they’re more like a spectrum with plateaus at each level. You may be at one of the plateaus or in transition somewhere in-between.

Personally, I believe I’m somewhere between the socialized and self-authoring mind. Over the last year I’ve let go of many external expectations I didn’t realize I was closely tied to and am beginning to find my own voice. My hypothesis of being between these two levels aligns with the research, which suggests that most of the U.S. adult population is in this same place.

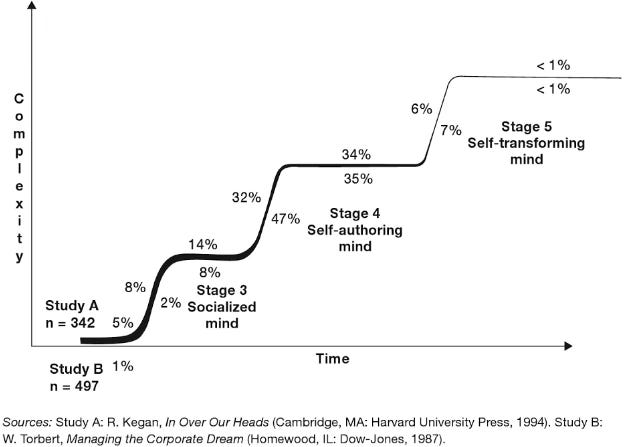

Two large-scale meta analyses of adult development studies illustrate that roughly 10% of the adult population has a socialized mind, 40% are between socialized and self-authoring, 35% are self-authoring, and only 7% are at or on their way to having a self-transforming mind.

Advancing one’s development

Kegan and Lahey created a process called “Immunity to Change,” (ITC) detailed in their book of the same name, to support individuals and teams in advancing their developmental progress. When I first read the book, it blew my mind. For most of my career as an organizational psychologist, I’ve been frustrated by implementing change efforts inside organizations that rarely stuck. The field of adult development and Kegan and Lahey’s ITC process explains not only why change efforts rarely work but how to make them work. It’s an elegant blend of personal and organizational psychology that’s appropriate for the workplace.

The process is called “Immunity to Change” because it uses the metaphor of an immune system to describe the mind. Change is hard even when we really, genuinely, want something to happen (like losing weight or exercising if it will support our health) because our minds like homeostasis - just like our physical immune system. Whenever we try to enact a change and struggle with it, there are subconscious forces keeping things as they are. It’s our mind’s immune system working as intended.

The ITC process involves working together to first come up with a change goal - something you really want to change about yourself that you’ve been struggling with. We then use a simple multi-step process to unpack what gets in the way of the intended change goal. We drill down and ultimately uncover a big assumption, or a core belief you have about yourself or the world that anchors your system in place. It’s called the big assumption because we typically hold these beliefs as truths. Discovering the big assumption is a leap forward in self-awareness - you can’t change unless you really understand what’s going on underneath the surface. Over time, we skillfully poke at and test the big assumption to see if it’s true or not (hint: they’re usually not).

These big assumptions are typically tied to our developmental level. As we start to clearly observe, expand, or overturn our big assumptions, our development advances. If we have a socialized mind, we move toward self-authoring. If we have a self-authoring mind, we move toward self-transforming. We become more equipped to see ourselves and the world - in particular our beliefs - more objectively.

Why adult development matters today

There is no “right” developmental level. Having a self-authoring mind is not inherently “better” than having a socialized mind. What matters most is whether your mind is equipped to meet the demands of your environment. For most of human history, when we lived in hunter gatherer tribes, having a socialized mind was sufficient. Today, the world is much more complex and uncertain. We are asking many of our employees, particularly knowledge workers, to show up to work in ways that require a self-authoring mind (e.g., take ownership of one’s work, be self-guided and self-evaluative) and we’re asking leaders to lead from a self-transforming mind (e.g., reimagine business models, skillfully address world-events with employees, customers, and shareholders). Yet when you look at the research, most of us are not where we need to be given what's being asked of us.

To quote Kegan, many of us are “in over our heads.” The only way to get our heads above water is to develop ourselves to meet the world we live in.

Today, through Bolderminds, I work with leaders and their teams who find themselves stuck. They’re struggling to implement a big personal or organizational change. They’re questioning the right decision to make. They’re navigating major transitions. Using frameworks from adult development, combined with emotional intelligence and practical tools from change psychology, I help them discover their own capacity for navigating uncertainty with wisdom and ease.